Photography has always been subjective. We believe what we want to believe.

Our history is edited, whether it’s words or photographs. There is no way to give a completely objective viewpoint. Every image we create or manipulate has the baggage of our life experiences, prejudices, culture and the time we live in. As a creative art form this isn’t a negative; it allows us to express an individual view of the world.

There are many tools available to photographers to tell a story. I’ve mentioned the language of photography before. Some tools are used at the time of capture, others in post-production. For example, when an image is created we decide the camera position and viewpoint, what’s included and excluded. We can also crop images afterwards to show a different point of view.

As a source of news or facts photography is subjective. Images can still be used as evidence, whether that’s reporting news or in a court of law. However what we trust is the photographer’s “word” that the image is true.

Photos as Evidence

When studying film some 30 years ago our class reviewed Emile de Antonio’s ‘Point of Order‘, a documentary on the 1954 Army-McCarthy Hearings. The hearings investigated whether the army was hindering investigations to uncover communists in its ranks.

Part of the evidence was a photo, revealed later to have been cropped to change its context. Senator McCarthy asks if it matters that a third person was cropped off a photo. US Army Secretary Stevens says: “tremendously, because it means someone is going to edit the information that is going to come before this committee“. This was the beginning of the end of McCarthyism.

Photos as News

This is not a question of truth but of belief. Science for example is credible because we have a common belief in it. Science is being questioned at the moment because our belief in it is being challenged, not because it isn’t true. Peer review scrutinises the facts. News is also being challenged; not its veracity but rather our belief in it.

Photojournalist Eugene Smith is acknowledged as the master of the photo essay. Smith’s photography changed the world for the better. He was obsessive with his photography, sometimes spending years to produce a body of work. Smith’s images are carefully crafted to tell the story. He used multiple lights to accentuate the mood he was trying to portray. In the darkroom Smith would spend an equal amount of time manipulating images, making areas of the image lighter and others darker. His post-production was so complex the final print would be re-photographed so that multiple copies could be made.

In his 1951 ‘Spanish Village‘ story for LIFE Magazine he created a image of a wake. It shows a family grieving over the body of a patriarch. The scene was artificially lit to emphasise the sombre mood. In the darkroom Smith enhanced the contrast and changed the gaze of the women’s eyes to better narrate the story. By today’s standards Smith’s images would be disqualified as journalism. Long term, history remembers Smith for his skills, passion and contribution to humanity, honouring his legacy with the ‘W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography‘.

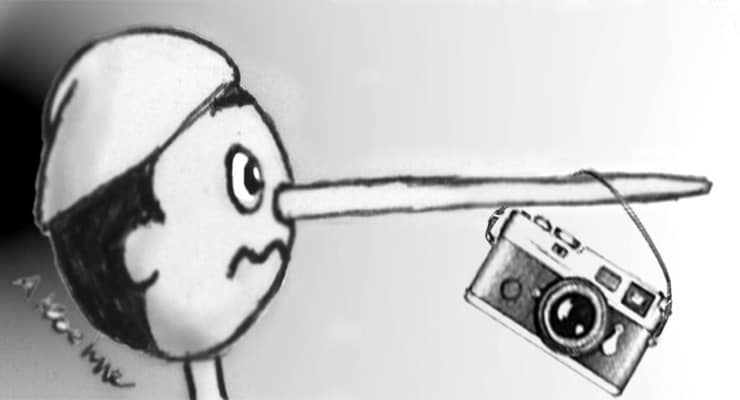

Cameras Don’t Lie, Photographers Do

Indeed anyone who handles images can lie. How they are captured, manipulated, presented can change its context. Sometimes for worse, mostly for the better.